In the never-ending arguments over the size of the government debt, one intriguing claim is that—allegedly—paying down the debt leads to an economic crash. This claim is particularly popular among the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) camp, who justify it on both theoretical and empirical grounds: First, they argue that sheer accounting proves government deficits are necessary for private surpluses, and second, they point to US history where, they claim, major government debt reductions were always followed by a depression.

I have elsewhere dealt with the claim that sheer accounting shows the folly of government debt reduction. In the present post, I’ll focus on the argument from US history. Contrary to the claims of the MMTers, I will show that there are plenty of examples of governments paying down debt with no ill economic consequences. And then, even focusing on the US specifically, I will show that there is no obvious connection between government debt reduction and economic crashes.

The MMT Argument Based on US History

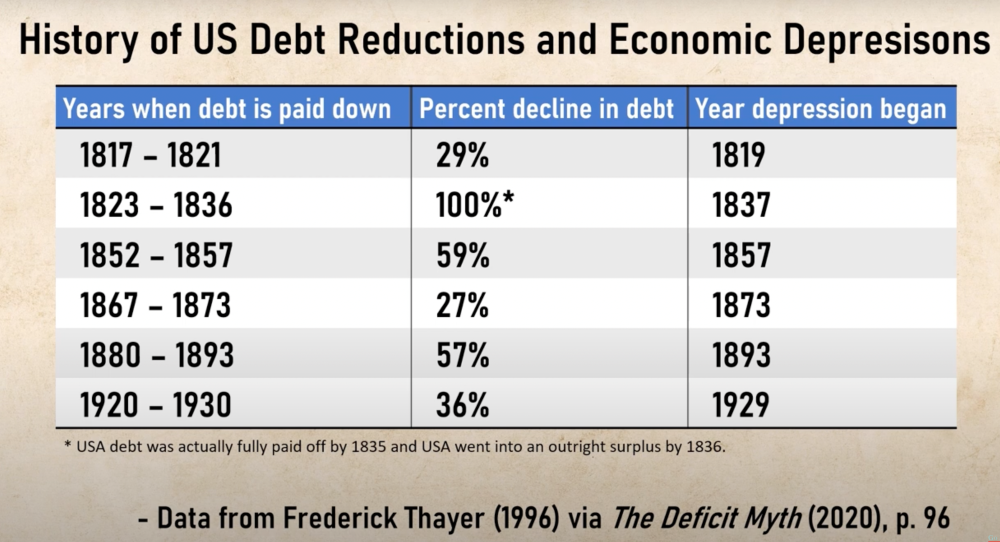

Stephanie Kelton, a leading MMT proponent, relies on historical US evidence in her book The Deficit Myth. Citing the work of Frederick Thayer, she argues that six periods of significant government debt reduction were all followed by a crash. On a YouTube video I found someone who had produced the following graphic, summarizing the case:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The table above is straightforward enough. The MMTers argue that you can argue with theory, but history doesn’t lie: Every time the politicians were foolish enough to pay down the debt—erroneously believing they were being “responsible”—they unwittingly crashed the economy, because (the MMTers claim) they didn’t understand the fundamental difference between a sovereign currency issuer and a regular corporation.

In the remainder of this post, I’ll rebut this appeal to history.

Examples from Europe and Canada

The easiest way to demonstrate that there’s no necessary linkage between government debt paydowns and an economic crash, is to cite several examples where governments tightened their belts and the economy did just fine, thank you very much.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, various governments initially ran massive budget deficits (while their central banks slashed interest rates and loaded up their balance sheets). Eventually they blinked and switched to so-called fiscal austerity. Plenty of Keynesians (like Paul Krugman and Christina Romer) warned that this would repeat the mistakes of the 1930s. In an unexpected twist, the European Central Bank (ECB) published a June 2010 bulletin, pooh poohing such critics and making the case for “expansionary austerity.”

As I quoted in an article from 2013, here is what the ECB bulletin reported about the European experience:

The empirical literature offers diverse results as to whether fiscal consolidations in the euro area have had expansionary effects on economic activity in the short run. With reference to the periods of sizeable government debt reductions mentioned above, expansionary fiscal consolidations are suggested in Ireland, the Netherlands and Finland. Looking at a broader range of experiences, it is found that around half of the fiscal consolidations in the EU in the last 30 years have been followed by an improved output growth performance in the short term relative to the initial starting position. (ECB June 2010 Bulletin, p. 85, bold added.)

Although I do not have the exact quotation, the ECB report went further and said that the countries experiencing successful austerity were those that reduced deficits primarily by cutting government spending, whereas the cases where austerity led to a weak economy involved the government raising taxes. This is completely consistent with a free-market economic perspective; when an economy is in a debt hole, raising taxes is a bad idea. But the fact that cutting government spending reined in deficits without causing a recession is hard to square with standard Keynesian views.

I am especially familiar with the case study of Canada, because I produced a 2012 study (with two co-authors) on their austerity episode. To quote from my 2013 article summarizing our findings:

By the mid-1990s, the Canadian federal government had been running deficits for two decades, with one third of federal revenue being absorbed by interest payments. A Wall Street Journal editorial on January 12, 1995 declared that Canada “… has now become an honorary member of the Third World in the unmanageability of its debt problem….”

Yet the Canadians swiftly solved the crisis with serious reforms. In just two years, from 1995 to 1997, total federal government spending fell by more than seven percent, while the budget deficit of $32 billion (four percent of GDP) was transformed into a $2.5 billion surplus. There were also tax increases, but the ratio of spending cuts to tax increases was about five to one. Canada’s federal government ran 11 consecutive budget surpluses, causing the debt-to-GDP ratio to plummet from 78 percent in 1996 to 39 percent in 2007.

In the decade after reform, Canada outperformed all the other G7 nations on economic growth, investment, and job creation. According to International Monetary Fund data, from 1996 to 2005, Canada’s average growth of real GDP was 3.3 percent, with the United States the runner up with 3.2 percent average growth, and the G7 excluding Canada averaging only 2.1 percent growth. Even in the short-term, Canada’s dramatic spending cuts (and moderate tax increases) in the mid-1990s had only mild side effects, causing only a temporary uptick in the unemployment rate.

And so we see that there are several examples from Europe and Canada in which governments switched from budget deficits to surpluses—in the case of Canada, cutting its debt-to-GDP ratio in half—while avoiding an economic crash. So clearly the situation is not as obvious as the MMTers would have us believe.

Now let’s turn to the US specifically.

The Case of the United States

First and most obvious: Although the Great Depression was indeed preceded by a string of budget surpluses (under the Coolidge Administration), the Great Recession of 2007-2009 was certainly not. Indeed, in the five years before the recession, the total outstanding federal debt increased by 45 percent. And likewise, for the awful recessions in the early 1980s, there was again a large increase in the public debt in the five years beforehand (namely, a cumulative 61 percent from fiscal years 1976 to 1981). In logical terms, we’ve thus shown that a government debt reduction is not necessary for a subsequent major economic crash.

Yet now let’s do the harder task and show that it’s not sufficient, either, based solely on the US data. (To remind the reader, in the section above I already showed government debt paydown doesn’t necessarily cause a recession in cases outside of the US.)

Before I look again at the table above, let’s be clear about the framing. Suppose someone claimed that rain dances caused thunderstorms. Now how would you, a cynic—presumably—of that hypothesis, go about disproving it? Well, if you could point to examples of major thunderstorms occurring without a preceding rain dance, then that would be a feather in your cap. (The analog of this, is the Great Recession example, where the economy crashed even though the government ran up the debt in the five years beforehand.)

But the defender of the Rain Dance hypothesis could say, “It’s true, other things can cause thunderstorms too, we’re just saying that the rain dance is one thing that can trigger it.”

So in order to rebut this claim, what would you need? You’d ideally want to find examples of people (such as the medicine man) doing the rain dance, with no thunderstorm then ensuing.

Now if you think about it, you realize that in practice, if you were really arguing with someone on this point, you’d need the person to be more specific about the time frame. Surely it would be vacuous if the medicine man did the rain dance, and then any subsequent thunderstorm, no matter how long we have to wait, thus justifies the practice. Surely at some point, we as a cynic can say, “It’s been too long, the thunderstorm should have occurred by now, so the rain dance didn’t work as advertised.”

With this framework in mind, look again at that table of US debt paydowns and economic crashes. In the first row, it shows a mere two years of government debt reduction were enough to (apparently) trigger the Panic of 1819. (Incidentally, the great Austrian economist Murray Rothbard wrote his doctoral dissertation on this episode, if the reader wants to see the Misesian theory of the business cycle applied.)

And yet, in the second row, we see that fourteen years of debt reduction (indeed, complete elimination) occurred, before the “resulting” crash. Or, in the fifth example, we see thirteen years apparently elapsed, before the debt reductions “caused” the crash.

Generally speaking, I think a much more straightforward explanation of the table is the following: Throughout its early history, the US dollar was tied to gold (and silver through 1873). When the government fought a major war, it borrowed to the hilt and ran up the public debt. But being on a hard money standard, the authorities knew that following the war, they had to gradually pay down the debt, just as any household or business.

Now interspersed in this pattern is the fact that the US economy suffered from a boom-bust cycle. The paydown of government debt per se didn’t cause busts, but obviously when a bust would occur, usually the government would halt the debt paydown. This is perfectly analogous to a household or business, where an emergency can lead to massive borrowing, but once the crisis is over, a string of surpluses must ensue. Yet if, while paying down the debt from the last crisis, the breadwinner or the company suffers a sudden drop in income, then the debt paydown will understandably be put on hold. Finally, when the US government abandoned the tie to gold, such that government debt paydown was no longer necessary, we would expect to see economic crashes occurring with no prior debt paydown.

I submit that my explanation fits the data in the table above much better than the MMT story. If my story were right, we would expect to see an example of the debt being completely paid off, over the course of many years, without the economy crashing. And yes, we do see just that—the second row in the table. I grant that my case would be even stronger if the debt had been paid off (by Andrew Jackson, incidentally) from 1823-1836, and then the next depression not occurring for, say, an additional five years. But the fact that the debt was completely paid off over the course of 13 years, with an extra bonus year of a surplus passing, before the crisis that this austerity was supposed to cause—simply strains credibility. With this amount of leeway, the MMTers can of course “prove” that government debt paydowns lead to a crash.

A Subtlety

Before closing, let me mention that there is a subtlety, whereby my own economic worldview would lead me to expect a correlation between government debt reduction and subsequent crashes. Specifically, if there is some engine that causes a boom-bust cycle (which in my view, is government interference with money and banking), then we would expect periods of unsustainable (apparent) prosperity to be followed by inevitable crashes. Other things equal, if the economy is in a bubble, we would expect relatively small government deficits (or even surpluses, such as during the Clinton years), followed by a crash.

Because of this subtle mechanism, it wouldn’t shock me if formal statistical analysis of US history revealed that government budget surpluses tend to be associated with weaker economic growth over the next (say) 3 – 5 years. But as all of my analysis above demonstrated, the connection would at best be a tendency; there is obviously no direct and necessary connection between government debt reduction and a bad economy.

Conclusion

In both theory and history, there is no reason to suppose that government debt reduction per se leads to weak economic growth. Despite the sophisticated arguments and appeals to history, common sense prevails: During normal times, responsible political officials should pay down the public debt.

Dr. Robert P. Murphy is the Chief Economist at infineo, bridging together the dependability of Whole Life insurance policies with the benefits of blockchain-based finance.

Twitter: @infineogroup, @BobMurphyEcon

Linkedin: infineo group, Robert Murphy

Youtube: infineo group

To learn more about infineo, please visit the infineo website